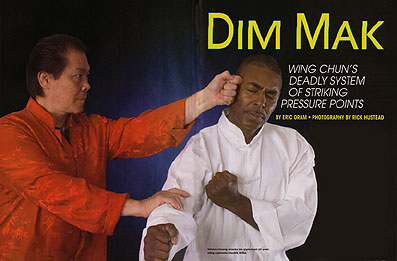

Wing Chun Dim Mak

It was a typical hot summer afternoon in Las Vegas in the mid-1980s. For some reason, my sifu, William Cheung, insisted that we train outside in the sweltering heat instead of in the air-conditioned workout room behind the house.

“Throw the punch,” he said after a quick bow.

Which punch, I wondered. But I knew better than to ask. I decided to just throw something and see what happened. And I’d better throw it: anything less than full-bore made him grumpy, and I didn’t want that.

So I punched.

Cheung deflected my jab and counterattacked more quickly than my brain could register. In a flash, he was back where he started, neutral, as if nothing had happened.

What had taken place? I knew he’d hit me, but I didn’t know exactly where.

Seconds later, the pain under my left arm brought me up to speed. Suddenly, I was no longer concerned about the heat. The pulsating, stabbing discomfort in my rib cage captured my focus.

“What was that?” I finally asked.

After a long pause, he answered, “A bil.”

Another pause followed. I knew some people used to call him “Bill” when he first came to the States, and for a moment I wondered if he was telling me that the technique was the “Bill surprise”.

“Bil jee!” he barked, as if reading my mind.

Now he had my attention. I’d heard of this finger-striking method, and Cheung was supposed to be very adept at it. In the two and a half years I’d been studying under him, however, I hadn’t heard much mention of these “secret” attacks. But the numbness in my ribs and arm seemed to confirm their existence.

“You’d better sit down,” he said.

“I feel fine,” I replied, as I broke out in a cold sweat.

“Sit down,” he repeated. “I need to work the points.”

“What points?”

“The pressure points to free the blockage on your heart meridian.”

“What blockage?” I asked.

“The blockage I just put there. Now sit!”

My knee felt a bit wobbly anyway, so I sat. He proceeded to manipulate a sequence of pressure points with his fingers. “So you know that it works. I needed you to feel the effects,” he said flatly. “But this will reverse them.”

Long pause.

“Good,” I finally muster. “What would happen if you just left it alone?”

“It’s not the right time of day to cause a full (heart) attack, so the effects are really minimal – plus it’s too hot, he said with a slight grin.

Again, I knew better than to ask additional questions.

As the feeling in my arm returned and the intense pain in my ribs eased, I took a moment to digest this: He’d hit me with his finger, and not very hard, but what a wallop it had packed! It was like being stung by a giant bee. But the use of the stinger didn’t kill this bee, and he was now removing his own stinger and extracting the poison.

Such was my introduction to dim mak.

***

Wing chun kung fu was created so smaller people could have an advantage when fighting larger people. Attacking pressure points is one of several methods for achieving this aim. That’s because the points, which number approximately 744 and are located throughout the body, rest along meridian lines. According to Chinese medicine, meridians circulate the blood and chi (internal energy) to the organs and bowels. This circulation is vital to health, for nutrients are required for cells to repair themselves and function properly.

When a pressure point is attacked, there’s a blockage at the affected area, which means chi cannot flow down the meridian and circulate to the organ it’s connected to. If the blockage is severe and goes untreated, the organ will eventually fail. Once that happens, the entire body is affected because each internal system is connected to every other system. Death can even occur – hence dim mak’s popular nickname, the “death touch”.

The pressure points are usually sensitive because most people don’t have their internal systems in balance. When a point becomes particularly sensitive, it’s the body’s way of saying there’s a problem with the associated area. Therefore, when one is struck or grabbed, it can be very uncomfortable, if not painful, and it can have long-term effects.

It doesn’t take much force to affect a point and its related organ or bowel. That’s what enables a smaller person to stun a larger and stronger attacker long enough to create an opening for a power move, submission, takedown, knockout or escape. But there’s a catch: To be effective, an attack must be very accurate. And because it will probably have to be executed on a moving target – one with dangerous hands and feet attached – accuracy can be difficult to achieve.

The Solution

A primary principle of wing chun is using the arms for simultaneous attack and defense. That enables you to accomplish three objectives:

- Make your counterattack instantaneous. Most wing chun blocks are followed by a near-simultaneous strike, which puts your opponent back on the defensive. He must defend himself instead of continuing to hit you.

- Guard the path of the most immediate threat while you attack. You protect yourself with one arm and attack with the other. In doing so, you …

- Control the elbow of your opponent’s arm with your checking/blocking arm while you counter. That facilitates attacking his balance while you exploit the opening.

That final objective lies at the heart of making pressure-point striking effective, for accurately landing a strike to a specific moving target requires you to impede the target’s movement. Only by stabilizing the target can you consistently hit the bull’s eye, so to speak.

The energy of the attack on the elbow is directed either forward (between the opponent’s toes) or backward (between his heels). That directs the pressure along the weak angles of his stance. When successful, it forces him to take an adjustment step to stabilize himself. He’ll be most vulnerable because he’s momentarily stationary.

- Therefore, controlling the elbow attacks the opponent’s balance, stabilizes the target and creates the opening you need. In doing so, you help ensure, at least for a moment, that your target will be there waiting for you.

Obviously, another key ingredient is timing. When defending, you want to catch your opponent at the peak of his commitment of his attack. That will ensure that he’s at his most vulnerable – he’s finishing the follow-through of his failed technique. In addition, once you’ve deflected the oncoming force, you use the continuation of your block to attack his balance along the weak angle of his stance.

It’s at this precise moment that you must be ready with your attack. As he’s stabilized, you instantaneously strike the pressure point, putting him on the defensive. Whether he blocks it or gets hit, he’s set up for your next attack, during which you pour into the opening you just created. Note that if you move too soon, the opening won’t be ready, and if you move too late, you’ll miss the opportunity – and possibly get hit. Therefore, you must develop the ability to time your interception and the immediate counterattack to the pressure point.

With practice, you’ll develop a clear understanding of the correct balance of defense and offense. The objective is to generate an instinctive response from yhour entire body, with the mental and physical components working as a team. Specifically:

- Your eyes direct you to the opponent’s elbow and target, and help you gauge distance, thus affecting your timing.

- Your center and footwork move you to the correct distance and angle at the right time.

- Your arms deflect the attack, pressure the opponent’s elbow and stun him.

- Your mind puts it all together by aligning each aspect, then getting out of the way so they can flow.

With practice, you’ll be able to respond without thinking. You’ll develop an instinctive understanding that encompasses the elbow you’re checking and the target you’re striking. Awareness of this relationship enables you to stay connected to the processes that lead to success.

Tools of the Trade

The main striking weapons of dim mak are the fingers, aka the bil jee techniques. The first key to using the fingers effectively is to keep them straight and tight. If you spread them – and especially if you’re a beginner – the energy and power you’re trying to release won’t make it out. Plus, your fingers are more likely to buckle if they’re separated.

The wrist is another crucial element. You approach the target with your wrist and fingers straight. However, when your digits make contact, you move your wrist up or down, left or right, to dissipate the back force. If your wrist stays stright, your fingers will have to absorb 100 percent of the back force, often resulting in their being jammed or broken.

Next is conditioning. One method for developing power in bil jee strikes involves hitting buckets of sand, pebbles, dried rice or dried beans. The repetitive motion conditions the fingers to move through resistance but provides enough give to allow you to still push through. Makiwara striking boards can also be utilized, but they should be reserved for more advanced workouts and better-conditioned fingers. Outlining all the components of a comprehensive conditioning program is beyond the scope of this article, but its importance shouldn’t be overlooked.

Ultimately, though, pressure-point attacks are intended to be used on sensitive or soft-tissue targets. Therefore, a little conditioning goes a long way.

These training methods also develop your chi through the repetitive intent sent through your fingers with each push into the sand, rice, etc. Once you begin putting your mind and body into each repetition, the chi will follow.

An additional benefit of using your fingers to strike is gaining reach. Extending them can add inches to your reach, making it possible to cover a greater distance than you could with a fist or a palm, and that can negate any advantage a long-armed opponent may have. Furthermore, you can use that extra reach to access more angles than you can with a fist or palm.

Another tool that’s often used in pressure-point attacks is the phoenix knuckle. It’s formed like a fist but with the knuckle of your index finger protruding. The orientation of your hand enables you to strike with nearly the same confidence you enjoy while punching, and it concentrates energy into a single point: the one knuckle.

This strike can sldo be conditioned through the use of sandbags, pebble-filled buckets and makiwara boards. Additional training can come from doing push-ups on your index-finger knuckles. You’ll lost a few layers of skin, but the callouses that form will improve your capacity for continued conditioning.

Points and Times

Within the art of wing chun, dim mak uses a short list of pressure points. Each lies along a specific line: the heart meridian, the small-intestine meridian, the bladder meridian, the kidney meridian, the circular-sex meridian, the triple-heart meridian, the gall bladder meridian, the liver meridian, the lung meridian, the large-intestine meridian, the stomach meridian and the spleen meridian.

An important and often misunderstood facet of dim mak is the time at which attacks are used with the greatest effect. Each organ has an associated time of day when it’s weakest and, therefore, most vulnerable. If you attack a point during this period, the meridian will slow or stop, and the organ can fail. In extreme cases, death can result.

It bears repeating that pressure points are often sensitive already, so even if they’re struck outside their time zone, your technique can still be effective. The pain can stun your opponent, setting him up for a more powerful blow or opening an avenue of escape.

The ultimate goal of dim mak is, in the immortal words of Muhammad Ali, to “float like a butterfly and sting like a bee.” Just like William Cheung demonstrated so convincingly on that hot summer afternoon in Las Vegas.

About the author: Eric Oram is a senior disciple of Grandmaster William Cheung. A wing chun kung fu instructor for more than 20 years, Oram is also a fight choreographer, actor and frequent contributor to Black Belt magazine.