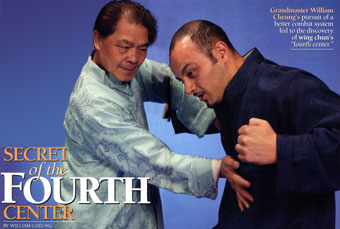

Secret of the Fourth Center

By Grandmaster William Cheung

(extracted from “Inside Kung Fu” magazine, March 2005)

Grandmaster William Cheung’s pursuit of a better combat system led to the discovery of wing chun’s “fourth center.”

For thousands of years ancient martial arts masters have attempted, with varying degrees of success, to refine the most basic aspect of fighting: protecting the fighter’s “centerline,” or “jong zin,” which is the most vulnerable part of the body. It is not coincidental that martial arts have developed many theories related to “lines of force” or “centers of energy,” often expressed as the body’s “meridians” or “axis lines.” These all are related to the essential interactions among balance, harmony and explosive power.

So, stance, poise and pervading calmness, established by supreme self-awareness, are formidable skills prerequisite to the martial artist as opposed to the brutish streetfighter. The masters, however, have always linked their arts with the real world, and the concept of “jong zin” recognizes the paramount importance of protecting yourself so you can fight. They regarded the most vulnerable section of the body as the “center” or “centerline.”

If an opponent lands a damaging blow first, then your ability to counterattack efficiently is impaired. Some martial arts actually emphasize the capacity to absorb blows and still counterattack, but to my mind, for various philosophical and practical reasons, this is not satisfactory. Essentially, a fighting sequence occurs in this order:

1. The Exponent’s Center

You initiate a form of “sao jong zin” that is “protecting your center,” employing various defensive strategies of stances according to the prescriptions of your particular martial art.

2. The Opponent’s Center

The opponent must protect his center – sao jung zin. By studying the “jong” – posing stance of your opponent, you can detect weaknesses if the center is unprotected. An attacking move is then employed directed at his center, which forces him to lose balance, retreat or reorganize for a counterattack. Your objective is to force your opponent to spend all his resources in defending and protecting his opening. Hence his chance of counterattack is diminished.

3. The Center of Confrontation

This is the classic “game of moves,” a conflict of move and countermove, in which each fighter attempts to deliver a telling blow, to achieve a “rhythm of ascendancy” (i.e., physical superiority). The fundamental aspect of this stage, which the pioneers of classic fighting recognized, is that it generates a rhythm of attack and counterattack in which, if you are delivering a blow, then in that instant your opponent can only defend and is unlikely to counterattack because he is operating on one centerline. Conversely, if you are defending appropriately, then you are absorbing or parrying an attacking move because you are using your centerline in “a center of confrontation.”

4. The Fourth Center

Many Asian martial arts have a profound philosophical or spiritual foundation that supports the physical structures of sublime physical skills. This is sometimes expressed as a harnessing of the potential released by a life of self-awareness and channeling experiences into positive energies. This desire to master negative and positive forces is an idea often expressed in Taoist writings. This was developed by the five founders of wing chun in the southern Shaolin Temple of Fok Kin province, China, 400 years ago. Their aim was to transcend what they regarded as the crude exchange of blows with too much emphasis on speed, strength and chance. With their innovation of “dai sai jong zin,” the fourth center elevated wing chun masters to simultaneously defend and counterattack.

The exponent employs this method on not only the first centerline, but also the central tangent, which is the second centerline and sometimes referred to as the fourth center.

As custodian of the Traditional Wing Chun discipline handed down by the legendary Yip Man, I have devised a simplified, more accessible version of the “fourth center.” This principle is superbly suited to the “soft” and subtle character of wing chun, but can be adapted to other styles.

Preparation:

“The Triad of Winning”

“The Triad of Winning”

Some martial enthusiasts come to the sport for the wrong reasons. Conditioned by the testosterone-fueled antics in escapist popular films, they look for a quick recipe for asserting their fantasies. Authentic martial artist have more interest in living well – to accord meaning and fulfillment to one’s existence.

Its discipline and training also provides a means of dealing with the physical stresses of living. This may involve being in a real conflict situation – where wing chun’s origins lie. Wing Chun is a way of life. If you are ever involved in a close-quarter combat in the arena or street, you need to appreciate the “Triad of Winning:” your heart, your eyes and the balance of your stance.

Heart:

To fight well you must have the will to win at all costs. This resolve should be matched by a capacity to repress anger, to achieve a state of anticipatory calm that all great athletes possess. Faced with a situation of great stress, the mind experiences a phenomenon called “survival stress” and initiates the release of adrenaline. Within seconds of this acid reaching the heart it begins to beat faster. When the heart rate increases to around 110 beats per minute, the pupils start to dilate, you lose rational mind functions, and you begin to lose the fine motor skills that govern coordination. As the heart races to 145 beats per minute, the body starts to lose complex motor skills; when the heart rate increases to 170 beats per minute, the body loses all fine and complex motor skills. The person is left with only gross motor skill, which is basic survival instinct. The body also releases a large amount of fat and sugar into the bloodstream to prevent the free flow of blood in the event of open wounds. The fat and sugar prohibits the free flow of oxygen in the blood and consequently, the muscles and vital organs. At this point, a person cannot think clearly or move fluently.

A fighter should be in a state of controlled calm. Training provides the body with the knowledge of accumulated stress, so that in an apparent contradiction, the body performs best while relaxed in a highly stressful situation. In fact, one definition of fitness says that you train muscles to relax. Traditional wing chun offers a specific chi meditation program to assist practitioners to achieve this goal.

Eyes:

Most of our information is gathered by our eyes (some studies suggest that around 75 percent of our daily information). It is important to train our eyes to look properly and effectively. In our discipline, I teach people to watch the leading elbow and knee of the opponent so they can track every move. In a straight punch, the elbow moves two and a half times slower than the fist, whereas in a round punch, the elbow moves four to five times slower than the fist. The opponent’s leading elbow and knee are further away from the defender’s eyes, which mean that they are easier to detect than the opponent’s fist and foot.

Balance:

Balance is the most important foundation for coordination, reflexes, speed and power. Without awareness of balance, technique would be inefficient. There are two types of balance: center of gravity balance, utilized, for example, by a kickboxer doing a spinning crescent kick; and dynamic balance, a form which helps a martial artist interrupt his movement at any time. As you take your stance, make sure your body weight is evenly distributed to optimize your potential mobility.

The Three Centers

Close Quarter Combat (CQC) requires protection of three centers.

1. The Center of the Practitioner –

Since most of the vital pressure points are situated in the middle of the body, it is important to protect the center of the body. It is impossible for the eye to see and for the body to react in time for the jab, unless you protect the center of your body.

2. The Center of the Opponent –

Knowing that all the vital pressure points and targets are in the center of the body, you must attack the targets close to the center of the opponent. If the opponent wants to utilize two arms, he must face his center toward the target (you). Thus, his center is available to you.

3. The Center of Confrontation –

In general, it is a martial artist’s convention that opponents must fight center to center. Attack is more effective when you put most of your effort into the center of confrontation.

In close quarter combat, one must attack to win. All things being equal, the more effective strikes one throws, the more one is likely to win. However, if the practitioner can direct the attack toward his opponent’s weaknesses, fewer strikes are needed. The opponent will use all his energy defending instead of attacking. Therefore I condensed the Traditional Wing Chun CQC system into a system called BOEC. Before contact, the exponent assesses the weaknesses of the opponent’s balance (B), opening (O), elbow (E), and arms or legs cross (C).

Balance: If the opponent leans on one leg, that is a weakness. That leg is not free to move until weight is transferred to the other leg. If you compare modern boxers to those of past generations, you’ll notice that modern boxers are balanced better because their center of gravity is evenly distributed.

Opening: When an opponent exposes his center, it creates an opening for the attacker. In the BOEC fighting system, we put pressure on the opponent to keep him on the defensive. The early traditional muay Thai fighters fought with their elbows on the outside, thus using their head as a tempting target. However, traditional muay thai fighters were not effective because they did not protect their “centers.” Now they have learned to keep their elbows in the middle of their bodies. This protects their heads and ribs, their “centers.”

Elbow: If one controls the elbow, one controls the fist. If one controls the knee, one controls the foot. Furthermore, when the elbow or knee is controlled, the balance of the opponent is also controlled. When most fighters put up their arm to defend their center, they expose their elbow and present a weakness. In the wing chun center guard, the elbow is not exposed, therefore there is no immediate target.

Arms and legs cross: This usually occurs when defending. Most martial artists would block with the inside arm toward the leading arm to execute a push block. By allowing the arms to cross over, it presents an opportunity for the opponent to pin the attacker’s arms. Some martial arts systems even cross their legs over, either at the front or back. This also gives the opponent an opportunity to compromise the attacker’s balance.

Secret of the Fourth Center

To get the most out of the BOEC fighting system, one should employ the fourth center. To understand the fourth center, it is important to understand the central tangent, because the fourth center is the central line. The centerline is the line coming out from the center of your body in the direction you are facing. The parameter of the central tangent is defined by how far from the left to the right or vice versa you can cross your arms in front of you.

The central tangent is where all the “lines” come out of your center when you face your opponent, and where you are able to cross your arms down and up at the wrists in front of you. The centerline is also one of the central tangents. Using the central line system allows you to use two arms at the same time for defense and attack toward your opponent without changing body direction. If you assume a side-on stance and veer too much to the right or left, then you can only use the leading arm for attack and defense, but the rear arm will be limited to defense.

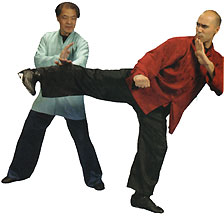

When dealing with your opponent on the open side, the blocking technique you use is at the centerline, so you must face the point of contact. This allows you to use the centerline to defend as well as the central line to counterattack simultaneously. In CQC, the fourth center lets you do that. If attacking on the open side, you could employ the fourth center by using the centerline to set up the pinning or trapping of the opponent’s elbows, the central line can facilitate the attack. By trapping the elbow on the open side and stepping toward the direction of the centerline where the defending arm is making contact with the elbow, the opponent’s balance is weakened and the free arm is kept at a safe distance.

On the blind side, to use the fourth center, one has to control the blind side on the opponent’s elbow by using the centerline so that one can employ the central line simultaneously.

What the fourth center shows is that it is not necessary to take two beats to block and counter. If you are facing the block, by using the centerline you can counterattack simultaneously using the central line. Your entire movement is one fluid motion.

Reflection

Close quarter combat is an exact science. The contest may last for seconds, with one wrong move spelling the end. When I began training in wing chun in 1951, it was a fun pastime. Then my passion for wing chun took over and I became competitive and a perfectionist. I started teaching professionally in 1973, and, for the first ten years, the pressure of running a business changed my sense of proportion. Gradually, the fun and passion started to fade. Only in the last five years has that sense of fun, joy and exhilaration come back into my art. It is through this joy that I continue to pursue the excellence that is wing chun kung fu.