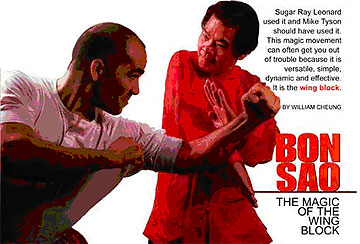

Bon Sao – Magic of the Wing Block

by William Cheung (extracted from Martial Art magazine, December 2002 )

Some 300 years ago, the Manchu army burned down the southern Shaolin temple. The Manchu were rulers by default, and their reign was characterized by the brutal measures they took to ensure that their delicate position was not upset.

The Manchu, for example, introduced the practice of binding women’s feet, which meant the women were dependent on their male relatives for their whole lives. To remove any danger of opposition, the Manchu also banned the practice of any martial arts. Soon thereafter, they discovered that the Shaolin temple was secretly training kung-fu warriors, and so they attacked the temple. Ng Mui, a nun from the southern Shaolin, fled to the south east of China. During her escape, she happened to pass through a fishing village where she observed the men fishing on the beach. While she was watching, a crane tried to steal the catch and a fisherman chased it with a stick. When the fishermen hit the crane with the stick, the crane, to Ng Mui’s surprise, lifted its wing. This movement deflected all the power of the stick. Ng Mui copied the movement of the crane and created the wing block, and she called it the bon sao.

WHY IT’S GOOD

WHY IT’S GOOD

The bon sao is superior to other blocks because it can be used as an offensive and defensive technique. In an offensive situation, the bon sao is used to jam the opponent’s elbow or to force him off balance. In defensive situations, the bon sao is applied from underneath the opponent’s striking arm or leg to destroy his balance. Thus, you can turn a defensive situation into an offensive situation quickly.

When you execute a bon sao, the blocking surface covers the area from the elbow to the knuckle, which is comparatively larger than used in other blocking techniques. The bon sao also deflects the force from your opponent’s strike, which shifts his balance and places him in a position in which he will be at a disadvantage. The bon sao is also versatile in such a way that it enables you to bring your guard hand into attack immediately. Or, the bon sao can follow the attack through on its own quickly and with minimal effort.

HOW TO DO IT

To maximize the effectiveness of the bon sao, you should lift your elbow, keep your fingers packed tight, and keep your wrist and forearm in a straight line. The protecting arm is known as the wu sao, and this is the same as the wu sao in the shil lim tao form, which protects the center of the body.

Protecting the centerline is critical because, if it is left open, your opponent can attack either in the center or around your arm, which leaves you with too much uncertainty. To reinforce the importance of this, let’s talk about reactions for a moment. It takes 2/10 of a second for a well-trained sportsman to react. A speedy punch can come even faster. If your center is unguarded when you fight, you are asking for trouble. When you protect your center, the attack can only come from outside of your arms, which is slower.

FORCE VS. FORCE

When you execute a bon sao and wu sao, your wrists are at the center of your body. This adheres to the principle of chil ying, facing the point of contact. This movement exemplifies one of the most important principles of wing chun, and that is do not fight force with force. If you do this, the stronger person will have the advantage. As you know, in a fight, a person has a better chance of winning if he has more opportunities to throw effective strikes. If he is wrestling with his opponent and fighting force with force, he is foregoing the opportunity to strike and this may lead to his downfall. So the secret is to create as much opportunity to attack as possible. Do not fight force with force and turn your defense into offense. This is paramount because you cannot win by defending; therefore you must attack.

| Principles of Wing Chun Defense By William Cheung PRINCIPLE NO. 1 PRINCIPLE NO. 2 PRINCIPLE NO. 3 PRINCIPLE NO. 4 PRINCIPLE NO. 5 |

IN ACTION

Let’s say you find yourself in a fight. If the force (or strike) is pushing forward, you should take one half-step to the side and let the force pass either on the open side or the blind side, and you should do this with the aid of a tan sao or yen sao and then finish with a pak sao.

If the force is going across, you should block with the bon sao and then do one of the following:

- Flip his arm over his head by using a larp sao or tan sao. His arm is on the other side of his body and the force has been deflected, creating an opening for a counterattack.

- You can also use a kan sao or another similar move and push his wrist downward to take the arm across the other side of the body. This will also create an opening for a counterattack.

- Finally, you can use a push block, the pak sao, and follow immediately with the tuen sao. Then take the arm to the other side of the body and create an opening for counterattack.

4 TIMES AS FAST

Because the bon sao needs the protection of the wu sao, at first sight, it looks a bit difficult to use. However, once you master the forward flow of energy when contact is made, the contact reflexes will guide you and you will be able to deal with any potential variations from your opponent. Eventually, you will become quite proficient in this technique and its variations. At that point, you will not want to replace it with any other block. It will always get you out of trouble when there seems to be nothing else, and the explanation is quite simple. When you lift your elbow, you will make your forearm move four times faster than it normally does, provided you do the technique correctly.

| The Mechanics By William Cheung When executing the bon sao, you must coordinate your feet and hips to get the most out of the technique. Following are some pointers to make sure your mechanics are sound.

|

TERMS

Pak Sao

A push block. The thumb is tucked in and the fingers packed together. The contact area is inside of the palm.

Kan Sao

Dissecting arm. The thumb is tucked in and the fingers packed together. The arm swings down from above and then continues out from underneath along the enterline. The elbow is in the center of the body at all times.

Jut Sao

Jerking block. The thumb is tucked in and the fingers packed together. The palm or the wrist can be used. The arm is jerked in toward you in a diagonal jerking motion.

Wu Sao

A guard. The thumb is tucked in and the fingers packed together. The arm is pushed out along the centerline. However, in the shil lim tao form, the wu sao is practised in the opposite direction, pulling in, to develop the isometric strength.

Chil Ying

Facing the point of contact. As with all of the fundamental principles of wing chun, when you execute a defensive block you are required to face this point to ensure that you are in the correct position.

Larp Sao

A circular block. The thumb is tucked in and the fingers packed together. The circular motion starts from underneath and ends on top of the opponent’s arm. The contact area can be the side of the palm, the palm or the lower forearm.

Tuen Sao

Threading arm movement. The thumb is tucked in and the fingers packed together. This is usually executed after you make contact with a pak sao and a jut sao. You slide your available arm along the blocking arm from underneath to make contact with the opponent’s arm. Be sure to not fully make contact with the opponent’s arm. Be sure to not fully extend your elbow. You must protect your center at all times.

Yuen Sao

Downward rotation of the wrist. Used to push the opponent’s arm away or to slip away to get to the other side of the opponent’s arm.

Tan Sao

The palm-up block. The thumb is tucked in and the fingers packed together. The elbow is on the centerline of the body and the energy is going forward. It is applied from underneath the opponent’s arm and slips on top.

Grun Sao

Combination of the bon sao and the tan sao. This movement is applied in front of you, so you must be looking at the point of contact.