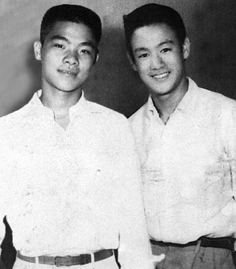

BRUCE LEE & WILLIAM CHEUNG

The Early Years

Before Bruce Lee was a martial arts star, he was a young actor, bullied by his schoolmates and often getting into trouble. In this 1992 interview, Wing Chun Kung Fu Grandmaster William Cheung recounts Lee’s early days of training and the difficulties he faced as a martial arts prodigy.

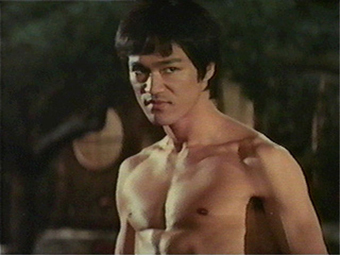

Today his influence is everywhere – in the spectacular leaps of an Ernie Reyes kata, in the sudden devastation of a Chuck Norris backfist, in the strategic theories of a Keith Vitali defence, in the unexpected angles of a Bill Wallace kick, in the delightful acrobatics of a Jackie Chan comedy; and even in the plastic nunchaku of the kid down the block.

Bruce Lee spent his early childhood in Hong Kong occupied by thee Imperial Japanese Army, and grew to adulthood during the troublesome post-World War II years, when the communist triumph on mainland China sent a constant stream of impoverished refugees into the tiny British Crown Colony.

Bruce Lee spent his early childhood in Hong Kong occupied by thee Imperial Japanese Army, and grew to adulthood during the troublesome post-World War II years, when the communist triumph on mainland China sent a constant stream of impoverished refugees into the tiny British Crown Colony.When Lee was six years old, the director of one of his father’s films spotted him hanging around the set and immediately asked to put the youngster to work in a major supporting role for an upcoming film. Bruce Lee’s film career was launched on that day.

“I first met Bruce at a party,” Cheung recalls. “My uncle knows a lot of Chinese operatic artists, and Bruce’s father was one of the most famous. So one day when I was about 10 or 11, my uncle said to me, “Come. We’re going to a place where a young movie star’s having a birthday party.’ So I said, ‘Wow, we’re going to see a movie star!’ Well, we went and Bruce was there. But at that first meeting I wasn’t really impressed with him because I was ignored completely. He was in the limelight. He probably didn’t even know I was there. We didn’t meet again until about a year later.”

By this time Lee was a child star living in an overcrowded city where literally millions knew his face, and he had to cope with constant challenges directed against his personal identity, especially from his peer group at school. On the one hand, there were those who expected him to be the streetwise gang leader that he portrayed in his films, and on the other had there were all those who expected his screen image to be a hoax. A film star had to be a sissy at heart, they believed, ad a personal victory over the Little Dragon’, as Lee was known, would be an easy way to earn a macho kind of respect.

By this time Lee was a child star living in an overcrowded city where literally millions knew his face, and he had to cope with constant challenges directed against his personal identity, especially from his peer group at school. On the one hand, there were those who expected him to be the streetwise gang leader that he portrayed in his films, and on the other had there were all those who expected his screen image to be a hoax. A film star had to be a sissy at heart, they believed, ad a personal victory over the Little Dragon’, as Lee was known, would be an easy way to earn a macho kind of respect.William Cheung remembers that Bruce Lee had a lot of trouble in his elementary school, in particular there was one overgrown member of his class who liked to intimidate the other kids. He used to extort their lunch money from them in exchange for ‘protection’. Eventually he got around to Lee.

‘All right, Little Dragon,” he said, “It’s your turn. I need some protection money from you, too.”

“Okay, sure,” said Lee. “I’ll fix you right up. But let’s go into the bathroom so the teachers won’t see us.”

The bigger boy followed Lee to the bathroom, but once inside, Lee abruptly shoved him against the wall, pulled out his pocket knife, and positioned the blade painfully against the boy’s stomach. The boy’s face turned white.

The bigger boy followed Lee to the bathroom, but once inside, Lee abruptly shoved him against the wall, pulled out his pocket knife, and positioned the blade painfully against the boy’s stomach. The boy’s face turned white.“Okay, now you take off your clothes,” commanded Lee. “All of them.”

When the boy had done what he was told, Lee grabbed his clothes and left, discarding them on the way home after school. Meanwhile, the boy locked himself into one of the bathroom stalls to be protected from the embarrassment of his nudity. Hours passed. He grew bored, then fell asleep.

By seven o’clock that evening, the boy’s parents had become panicky. He still had not come home from school. First they called the school, but nobody on duty had seen him. Then they called his teacher, who reported that she had not seen him since early that afternoon. Finally they notified the police.

The police began a major search of the neighborhood and school grounds. However, the boy was not found until much later that night when the drop in temperature awoke him. He began to scream frantically.

“Bruce got into a lot of trouble over that incident,” Cheung says simply. Indeed, the involvement of the police and the school administration of course came to the attention of Lee’s father. He became quite alarmed by the impact his son’s tough kid behavior and constant fighting were having on his studies, especially after the school asked Lee to leave. He made several attempts to combat the problem by trying to intervene in his son’s filmmaking career. But each time, the Hong Kong producers and directors dissuaded him.

The story of the bathroom incident quickly spread among the school kids throughout Hong Kong, gaining even greater respect and fame for the Little Dragon among his peer group. At the same time, William Cheung had already become quite notorious for his ability to beat elder students in battles of both brawn and wit. And since one of Cheung’s classmates was a member of Lee’s gang, the “Junction Street Eight Tigers”, a second meeting was arranged between the two.

“When I met up with Bruce again,” says Cheung, “he immediately started asking me questions about why I always won when I fought. I told him that I’d been doing this style [of kung fu] for a year, but that it was too rough for him… because he was a film star. He should look after his appearance. I also told Bruce that it was this particular style that was so good, and that we’d soon be organizing secret tournaments between it and other styles. He insisted that when we organized secret tournaments that he be allowed to come along and watch. But I didn’t take him seriously at all.”

“When I met up with Bruce again,” says Cheung, “he immediately started asking me questions about why I always won when I fought. I told him that I’d been doing this style [of kung fu] for a year, but that it was too rough for him… because he was a film star. He should look after his appearance. I also told Bruce that it was this particular style that was so good, and that we’d soon be organizing secret tournaments between it and other styles. He insisted that when we organized secret tournaments that he be allowed to come along and watch. But I didn’t take him seriously at all.”Shortly before his 13th birthday, Lee began attending his new Catholic school, La Salle College. Again, he both attracted and created his own trouble. On one occasion he nearly got his head knocked off by a junior kung fu stylist in a gang related exchange. Lee was furious. He could not bear the thought of losing a fight. He stormed home that day and announced to his mother that he wanted to be trained in the martial arts. He told her that he was being bullied at the new school and wanted to learn how to defend himself properly.

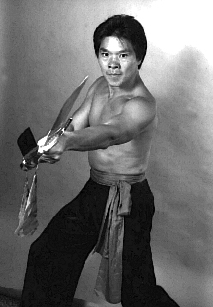

Lee’s mother agreed to give him the money for the kung fu lessons. He then hunted down Cheung’s instructor. However, Cheung did not believe that Lee would be a serious student. Lee persisted, and with some reluctance on an autumn day in 1953, Cheung took Bruce Lee to the Restaurant Workers’ Union Hall, where classes were held, and introduced him to the Grandmaster of Wing Chun kung fu, Professor Yip Man.

“Yip Man was very pleased to meet him because Bruce was a celebrity,” continues Cheung. “And Yip Man always had an appreciation for talent. So I left hi there, and Bruce began taking lessons straight away.”

Prior to his enrolment in Professor Yip’s classes, Lee had had no exposure to a serious fighting art. Lee promptly dedicated himself to a seemingly impossible pursuit – that of building his naturally frail frame into an awesomely effective fighting machine. His passion for kung fu bordered on fanaticism.

Meanwhile, William Cheung’s home life had become intolerable. His own exploits as a street fighter drew severe condemnation from his father, which in turn resulted in constant bickering. To diffuse the unhappy situation, Yip Man asked young Cheung, who had always been his favorite disciple, to live with him. Cheung jumped at the offer. And since Yip Man never taught the Wing Chun classes personally, Cheung earned his keep by being installed as one of the Grandmaster’s senior instructors.

However, despite Cheung’s instructor status, he still did not work with his most celebrated student. “I thought he was just learning kung fu because everybody was doing it. I still didn’t take Bruce very seriously. Then, shortly after we moved the school to a bigger facility in Kowloon, we started hearing complaints about Bruce beating up his seniors, as well as other people who were training with him. They became very upset because he was progressing so fast. He practiced every minute of the day. Even while talking, he was always doing some kind of arm or leg movement. That’s when I realized that Bruce was actually serious about Wing Chun.”

Now William Cheung, the other instructors and even Grandmaster Yip gave Lee the personal attention which was extended only to preferred students. A close friendship developed between Lee and Cheung, and they began to spend time together outside Yip’s classes.

“Bruce was also very, very fit,” explains Cheung. “Also he practiced Wing Chun very hard, and so always won his fights, although many times we really just outsmarted our opponents. Bruce took a lot of challenges. That’s the most amazing thing – he never backed out of any fight. In some situations I would have thought he’d be scared, but no, not him. Some of the other boys with us would run away. Bruce would be so angry with them afterwards that he would not speak to them because they did not have courage.”

One day William Cheung was shooting pool I Nathan Road’s second storey billiards room. Suddenly the calm of the room succumbed to the rapid-fire pounding of Lee’s ascending footsteps.

“Ah Hing, Ah Hing,” he cried. “They’re after me! A whole group of them!”

Cheung took another shot at the pool balls, then looked up. “Wait a minute, Bruce, you are in your own neighborhood. How do you know they are after you?”

“I know because I beat up one of them” Lee replied.

“Oh,” Cheung sighed. He put down his cue and walked over to a window. Outside, milling about the street, were about 50 members from one of the larger gangs. They could be recognized by the white handkerchiefs they wore to identify each other.

“Well, I see your problem, Bruce,” said Cheung. “But I think I know a way to get you out of this. Let’s go out there.”

Nathan Road is a major Kowloon artery. At that time of day, on any block, hundreds of people could be found walking down the street. When Lee and Cheung emerged from the billiards room, they immediately made the hostile gang suspect a neighborhood trap by the unhurried, cavalier manner in which they carried themselves. Wherever a group of gang members stood, Lee would wave at a nearby group of civilians. And since Lee was a well-known film personality, all the people walking down the street would recognize him and wave back. Soon the gang members were convinced that they were outnumbered, and disappeared.

By the end of 1956, Bruce Lee had become a serious problem for Yip Man. “Because he progressed so quickly, he became a threat to some of the seniors,” says Cheung. Yet according to custom, a kung fu student was supposed to remain humble and subservient to his seniors. To do otherwise was considered a direct combat challenge. Since Lee only respected the knowledge and fighting abilities of Yip Man and Yip’s appointed instructors, he refused to comply with the arrogant whims of his seniors. Instead, he would challenge and defeat them easily.

Cheung continues; “Then they found out that he had a little bit of European blood in him (his mother is half German). They decided to use that to stop Bruce from training at the school, and put a lot of pressure on Yip Man who was a traditional person. He did not believe that the art should be passed on to Westerners.”

As Yip Man was a poor businessman and money slipped through his fingers, the students had formed a committee collecting the school fees to pay rent and a personal allowance from Yip Man. These senior students threatened to reduce Yip’s personal allowance if he did not dismiss the Little Dragon.

“So very reluctantly, Yip Man agreed,” admits Cheung sadly.

“Quietly, Yip Man was proud of Bruce, even before he became a popular kung fu star. There was a friendship between Yip Man and me, Bruce and me, Bruce and Yip Man.”

Lee’s feelings for his master were made clear in 1967 when he said, “Before I discuss jeet kune do, I would like to stress the fact that though my present style is more totally alive and efficient, I owe my achievement to my previous training in the Wing Chun style, a great style. It was taught to me by Mr Yip Man, present leader of the Wing Chun clan in Hong Kong where I was reared.”

Yip Man knew that Cheung and Lee were close friends, so told Cheung, “You give him some practice.” Cheung knew that his master’s words were a personal mandate to complete Bruce Lee’s training in Wing Chun. After Lee left the school and Cheung moved back home with his parents, Lee trained almost exclusively with him.

“By that time I had learned almost everything there was in wing Chun,” relates Cheung. “All I needed was time to practice. Bruce started visiting me at my parents’ farm in the New Territories every weekend when he wasn’t working on a film, until I left for Australia.”

“By that time I had learned almost everything there was in wing Chun,” relates Cheung. “All I needed was time to practice. Bruce started visiting me at my parents’ farm in the New Territories every weekend when he wasn’t working on a film, until I left for Australia.”Cheung reveals that he deliberately structured these training sessions with Lee so that they became experimental in nature. His reason was an important one. During the several years that he lived with Yip Man, Cheung discovered that the Grandmaster withheld key elements of the Wing Chun system from his commercial instruction. Specifically, Yip Man did not teach the system’s authentic footwork, nor its applications in closing the gap through Wing Chun’s ‘theory of four fighting ranges’. Instead he taught modified patterns that were quite rigid, quite immobile, and quite impractical. The same patterns are still taught to Wing Chun students throughout the world today.

Yip Man made Cheung vow that he would never teach the complete Wing Chun system for as long as Yip remained alive. So Cheung engineered practical situations for Lee which emphasized the weaknesses in the modified Wing Chun. “I was in a situation where I had to influence Bruce to ask himself a lot of questions,” explains Cheung, “because I could not show him, and even made him irritated so that he would sit up and think, ‘Why?’ trying to find out himself.

In 1958, one of Lee’s school teachers tried to re-channel the young film star’s obsession with street fighting into a more respectable direction, convincing Lee to join the school boxing ream. Lee agreed, but refused to train with the team, and appeared not to be training at all, leading his classmates to think he was crazy. Behind the scenes though, Lee entrusted his tournament preparation to William Cheung. “I trained him in boxing for the boxing contest,” confirms Cheung. this was his first boxing fight so he was very inexperienced. After the first round he settled down, and won very convincingly.

“Bruce was very competent by then. He had a few contests with other styles, and enjoyed beating them. His understanding was much greater than the people who were teaching. He was always criticizing the modified footwork, saying, ‘Look, why is it like that? Why do I have to do this?’ But I could not tell him. I’d given my word. He never knew,” relates Cheung.

Years later in the film Return of the Dragon, Lee would play a country bumpkin who was trained in Chinese boxing on a farm in the New Territories. The picture was written and directed by Lee, and the origin of the story is an obvious tribute to the training experiences Lee had with William Cheung.

Although the summer of 1958 proved very productive for the Little Dragon, giving a critically acclaimed performance in Orphan, Lee’s first starring role, autumn brought another confrontation with the police. “This is the incident which caused him to stop seeing the Junction Street Eight Tigers and eventually to come to America,” recounts Cheung. “They did some shoplifting and we were taken with them. They ran so we had to run too, but we hadn’t taken anything.”

Shortly afterwards, both William Cheung and Bruce Lee decided to make a new start at life, away from the street gangs of Hong Kong, by attending school overseas. Cheung joined his brothers in Australia, whereas Lee, who had been born in San Francisco, returned to America and took his rightful place as a US citizen.

Extracted from “Best of Blitz” Collector’s Edition Vol. 3 www.sportzblitz.net